Since I started collecting cookbooks, I realized that I could dig below the surface of any single one and find something intriguing about it. It's always more than a cookbook; it's often a fascinating story and a unique piece of history.

Over and over again, I find the cookbook's author is frequently a woman or group of women; I do some searching, and there's always more to the story. These discoveries are why I dig for cookbooks and continually feel women's history is hiding inside them.

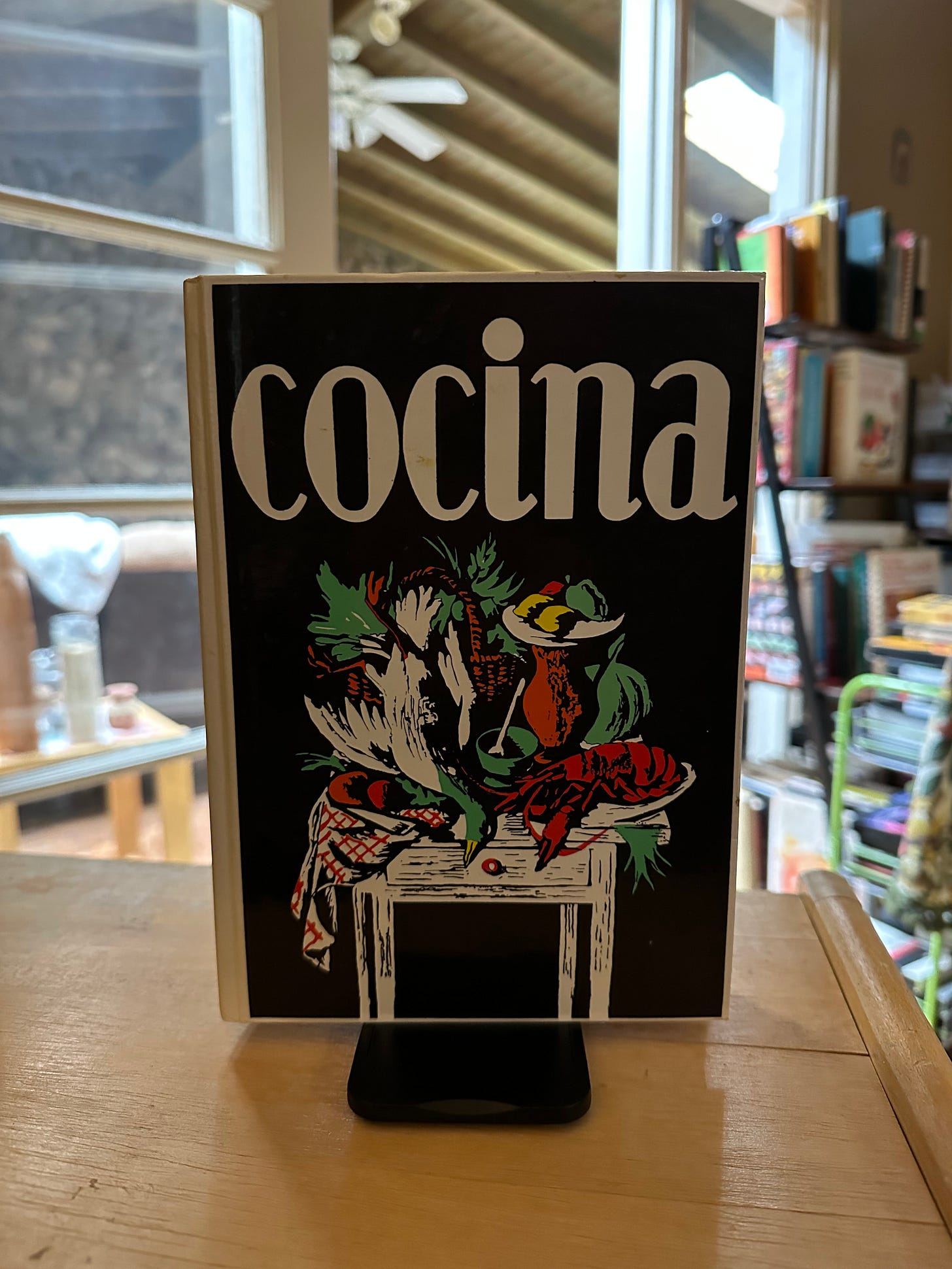

This week I worked at a house in the South East heights full of knick-knacks. There was an unending series of bins for me to unpack, stage, and price. I made some time to go through the books in another room. A cookbook called Manuel de Cocina (Madrid) was on the shelf, printed in Spain in 1982.

When I got home, I took a closer look. Since it's in Spanish with little information on the title pages, it took me some time to identify it and find out who was behind its publication.

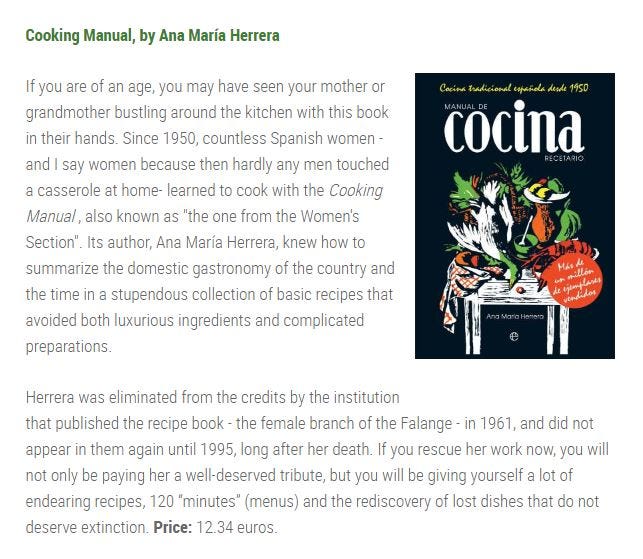

I finally found the book online and discovered that it had been considered an essential cookbook in Spain since its publication in 1950. Mothers and grandmothers have relied on it for basic cooking and classic Spanish dishes ever since.

Excerpt from El Comidista article Twelve Simple Cookbooks to Download

Manuel de Cocina is still in print. My copy’s author is listed only as “Colectivo.”

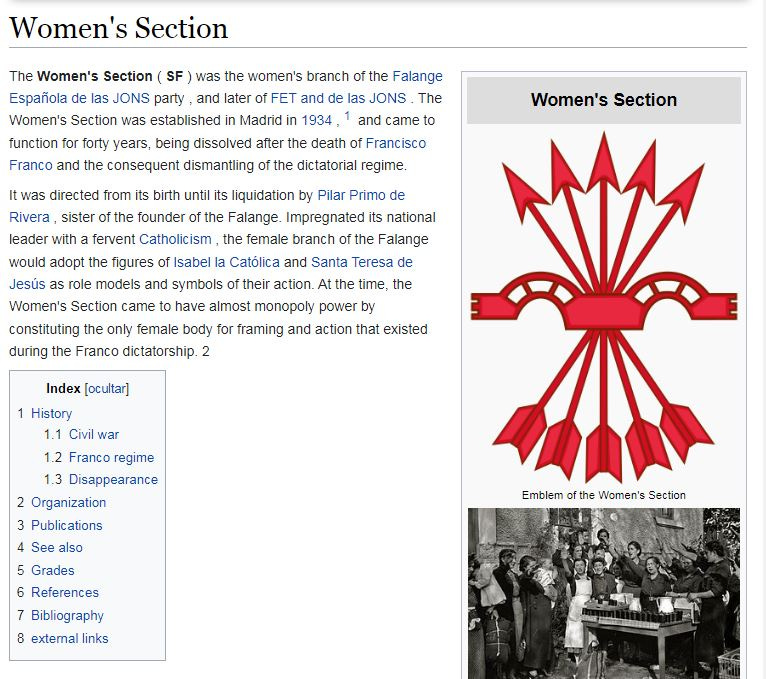

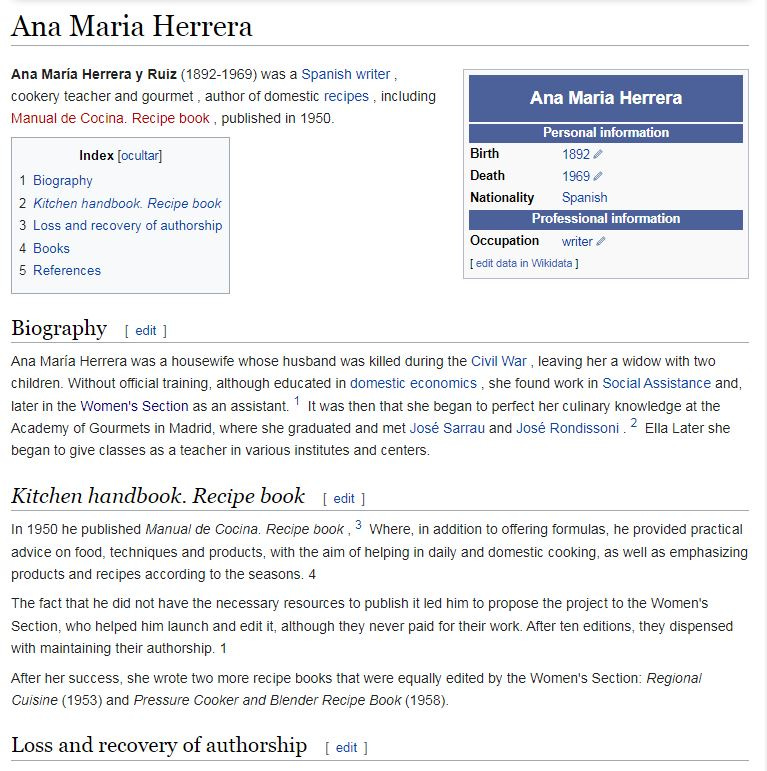

Ana María Herrera’s authorship was eliminated in 1961, replaced with “Collective” for the Women’s Section—La Sección Femenina, a branch of the Falange political party and part of Francisco Franco’s fascist dictatorial regime in post-War Spain.

Using her domestic skills as a housewife, Ana María Herrera found work as an assistant in the Women’s Section after the death of her husband in the Spanish Civil War. She was able to go to culinary school and become a teacher.

At the time, the Women's Section came to have almost monopoly power by constituting the only female body for framing and action that existed during the Franco dictatorship.

Women's work inside the home has often been used for political and ideological control of homes and families by institutions and governments for a long time. These strategies and courses of action have altered women's lives. They have become the lens through which I research colonialism, capitalism, and conservatism.

Falangism places a strong emphasis on the Roman Catholic religious identity of Spain,[5] although it has held some secular views on the Catholic Church's direct influence on Spanish society,[5] since one of the tenets of the Falangist ideology holds that the state should have the supreme authority over the nation.[6] Falangism emphasizes the need for total authority, hierarchy, and order in society.[6] Like fascism, Falangism is anti-communist, anti-democratic, and anti-liberal.

Ana María’s cookbook contains practical food advice, products, and techniques that help everyday home cook’s with available seasonal ingredients. Since she did not have the means to publish the cookbook, Ana María proposed the book to the Women’s Section, to help get it published.

After the death of Francisco Franco, the change and transition of government led to the dissolution of the Women's Section. The authorship was given to the Ministry of Culture in 1977 after the Women's Section had been eliminated. Prior to that, it was the only mass organization of women to exist during the Franco regime.

(In July 1977, the new government transferred some of the services to the newly created Undersecretary for Family, Youth, and Sports.)

In 1995 with the help of her grandchildren, long after her death, the cookbook was rightfully re-credited to Ana María Herrera. In addition, they gave her the recognition she deserved for her long-lasting impact on the culture and cuisine of Spain.

Other cookbooks by Ana María Herrera:

Regional Cuisine (1953)

Pressure Cooker and Blender Recipe Book (1958)

This is all very fascinating. Enjoyed reading your research. I, too, am interested in the stories behind cookbooks.